Project Overview

Human reactions to design aesthetics are deeply rooted in cognitive and psychological processing (Palmer, et al, 2013). Perception plays a crucial role in aesthetic response, and on Earth, where gravity provides a fixed frame of reference, humans, in most settings, interpret design aesthetics from a single orientation (Greenland & Morgenstern, 1991). However, in microgravity environments, such as deep space or planetary orbit, this constraint is removed and objects, as well as their aesthetic design choices, are viewed from multiple directions.

Given these unique conditions, this project explores the interaction between orientation and aesthetics for application in future space systems. Specifically, I aim to design a table that maintains a consistent aesthetic appearance regardless of the user’s viewing angle. This work will not only address a practical design challenge but will follow the aesthetic of neuroaesthetics to achieve this goal.

Background

Research in cognitive science has demonstrated that orientation significantly influences perception. One striking example is the Margaret Thatcher illusion, as shown below, where an inverted face appears normal until flipped upright, revealing its distortions (Thompson, 1980). This phenomenon underscores how deeply ingrained perceptual biases are in human cognition.

While human perception of faces is more complex than that of inanimate objects, similar principles apply to design aesthetics. Neuroaesthetics, a field that examines the intersection of neuroscience and aesthetics, explores how design elements influence human cognition, emotion, and behavior (Chatterjee & Vartanian, 2014). This approach has started to gain traction in the world of architecture and interior design to create function driven spaces. The images below show the use of this aesthetic in the design of hotel rooms designed to evoke specific emotional responses and human behaviors depending on the room.

Building upon these insights, this project extends neuroaesthetic principles into the realm of space design, considering how this aesthetic can be used when a single gravitational reference is removed.

Application to Microgravity Environments

Inspired by neuroaesthetics, I developed the concept of “directionless design,” a branch of neuroaesthetics which is concerned with the perceptual based aesthetic of objects. The term directionless is used to describe the lack of singular direction from which the aesthetic can be perceived. The goal of directionless design is to maintain a consistent human reaction within a space, regardless the directionality or orientation of the viewer.

To better understand how perception shifts in microgravity, I researched similar design principles rooted in terrestrial applications. One such principle is the ambigram—a graphic representation that remains legible from multiple orientations. Letters and numerals like 0, 8, H, I, S, and O exhibit rotational symmetry, making them effective ambigrams. A well-known example is the SONOS logo, which retains its visual coherence when inverted. Despite their common use in typography, ambigrams remain largely unexplored in three-dimensional objects.

Plans for Final Project

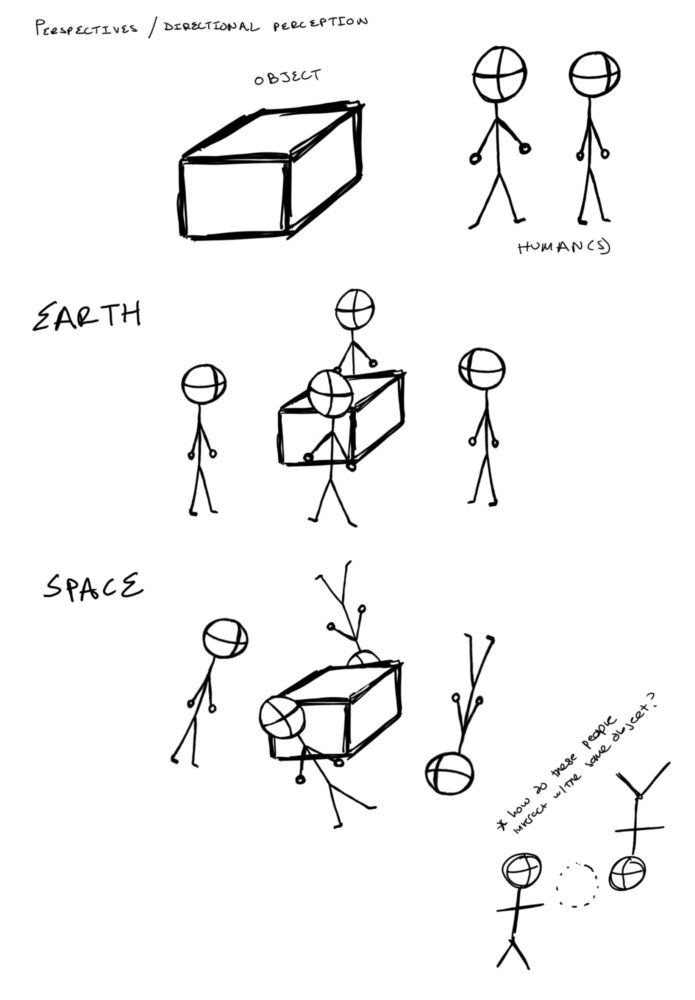

To test these principles, I aim to create an object that maintains a consistent aesthetic response regardless of the viewer’s orientation. My initial ideation process here involved a thought experiment illustrated below.

I first depicted stick figures around a box to simulate how multiple people view an object on Earth. Then, I rotated each figure to different angles to represent how the same individuals might perceive the object in microgravity. To remove abstraction from this visualization exercise concrete, I placed the stick figures inside the habitable module of the Vast Haven1 space station, as shown below.

I first depicted stick figures around a box to simulate how multiple people view an object on Earth. Then, I rotated each figure to different angles to represent how the same individuals might perceive the object in microgravity. To remove abstraction from this visualization exercise concrete, I placed the stick figures inside the habitable module of the Vast Haven1 space station, as shown below.

This experiment revealed a critical design issue: the conventional table, as used in the Haven1 module, in a microgravity environment would elicit inconsistent aesthetic responses. For example, an observer positioned “upside down” relative to a flat table might perceive an unappealing underside, akin to seeing gum stuck beneath a desk, and who wants to see that on their multi million dollar vacation in space? Recognizing this challenge, I decided to use it as the foundation for my project.

For my final design, I will apply directionless design and neuroaesthetic principles to create a table or workstation optimized for use in microgravity environments. The goal is to ensure that users experience a visually harmonious object with clear design aesthetic from any perspective.

Detailed Description

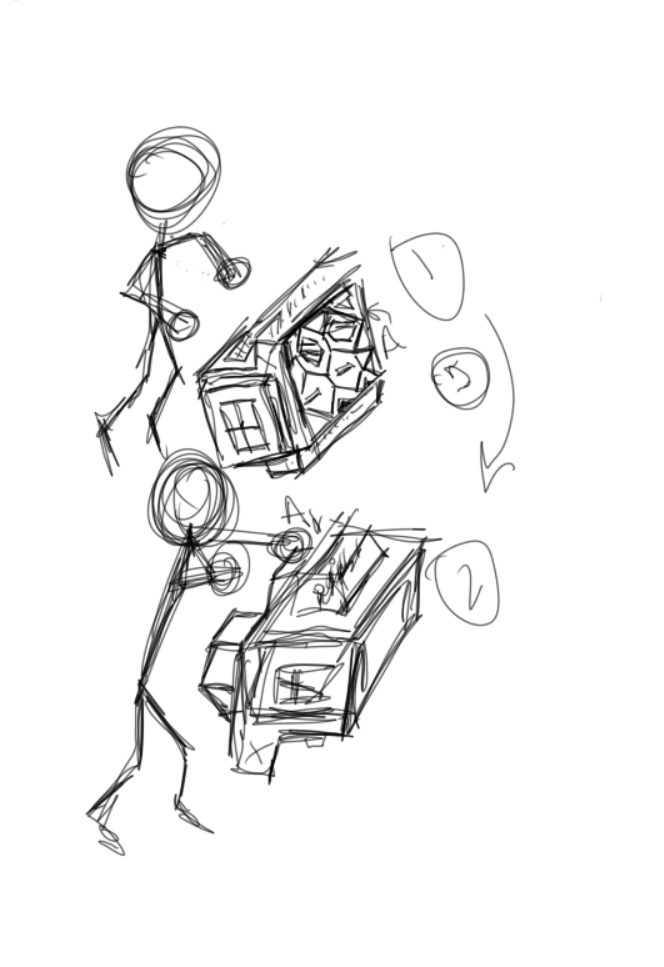

The images below illustrate the evolution of this concept. Initially, I considered how a table or workstation could be utilized from multiple angles rather than a single fixed position.

As my design matured, I explored how different functional systems could be integrated into each face of the object.

While constructing such a complex design poses challenges, my primary objective remains creating a visually coherent object that maintains aesthetic appeal from all viewing angles. The workstation will be mounted on a pole with a gimbal mechanism, allowing it to be articulated into multiple orientations, similar to its expected use in microgravity. This feature will encourage users to interact with the object from different perspectives, reinforcing the core principles of directionless design.

I plan to use a combination of upcycled and purchased materials. The longest lead-time components may include custom-printed panels. To refine the design, I will prototype using printed PVC and poster board, providing a cleaner appearance and better demonstrating the intended aesthetic.

Timeline and Design Process

My timeline is shown below; note that the timeline is overlaid on to the double diamond design process (diamonds not shown due to how small the text got). As can be seen in the structure of this post, I utilized the double diamond process as I went through the research and ideation phase, and continue to do so as I move to initial prototyping and final assembly.

References

Chatterjee, A., & Vartanian, O. (2014). Neuroaesthetics: A coming of age story. *Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 26*(2), 235-242. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00535

Design principles: Visual perception and the principles of gestalt — smashing magazine. Smashing Magazine. (2014, March 29). https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2014/03/design-principles-visual-perception-and-the-principles-of-gestalt/

Greenland S, Morgenstern H. Design versus directionality. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44(2):213-5. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90269-f. PMID: 1995777.

Palmer, S. E., Schloss, K. B., & Sammartino, J. (2013). Visual aesthetics and human preference. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 77–107. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100504

Thompson, P. (1980). Margaret Thatcher: A new illusion. *Perception, 9*(4), 483-484. https://doi.org/10.1068/p090483

1 Comment. Leave new

This is a fascinating design concept, and I’m learning something new! It seems like it will be a challenge to pull off, given that you won’t be making this in a microgravity environment, but I like your pole and gimbal solution for this. Do you have any plans right now for the functionality of the table from various orientations?