The Need for Directionless Design in Space Environments

Despite significant advancements in space technology, design considerations for microgravity environments have not evolved to fully accommodate the unique physiological and psychological needs of astronauts. On Earth, design is fundamentally constrained by unidirectional gravitational forces, which inform both functional and aesthetic choices. Objects are conventionally created to be used in a singular orientation relative to Earth’s gravitational field. However, in microgravity—particularly in deep space travel or planetary orbit—this constraint is removed. Thus, the absence of a fixed gravitational frame of reference necessitates a reevaluation of traditional design paradigms.

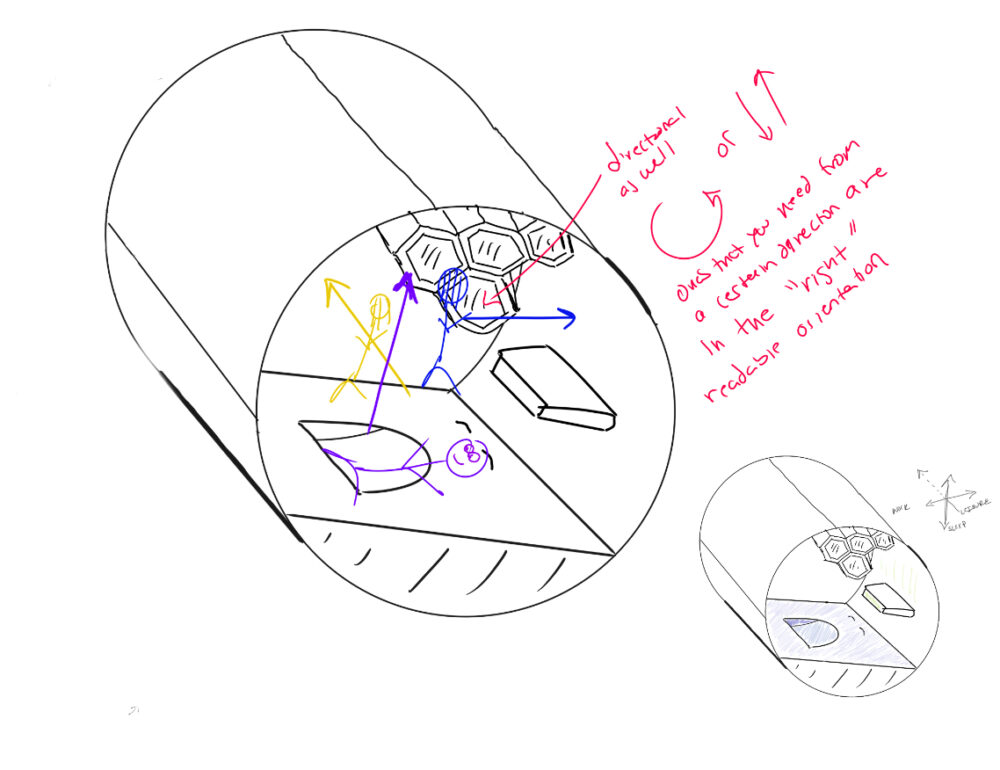

In microgravity, humans are not limited to a single spatial orientation, which raises critical questions about how design can enhance adaptability and overall comfort in this environment. I propose the concept of “directionless design” as a derivative of neuroaesthetics—an aesthetic framework specifically tailored for nondirectional spatial experiences. The primary objectives of directionless design are threefold: (1) to improve human adaptability to a microgravity environment (2) to encourage the exploration of human behavioral norms in microgravity, and (3) to create objects which embrace and are natural to human behavior in microgravity.

Theoretical Foundations: Ambigrams and Visual Perception

The principles of directionless design have roots in terrestrial design concepts, particularly the study of ambigrams. An ambigram is a graphic representation that retains legibility from multiple orientations. Certain numerals and letters, such as 0, 8, H, I, S, and O, exhibit rotational symmetry, making them effective ambigrams. One of the most well-known commercial examples is the SONOS logo, which maintains visual coherence whether viewed upright or inverted. Despite the prevalence of ambigrams in logo design and typography, their application in three-dimensional objects remains largely unexplored.

Expanding upon this, directionless design can integrate visual illusions to further engage human perception. The brain is a highly visual processor, and its interpretation of orientation is significantly influenced by contextual biases. The Margaret Thatcher effect, for example, demonstrates how facial recognition is dramatically impaired when images are inverted, emphasizing the role of orientation in cognitive processing (Thompson, 1980). By leveraging visual processing tendencies, directionless design can be optimized to minimize perceptual dissonance in microgravity environments.

Viral picture of Adele demonstrating the Thatcher effect; our brains struggle to identify abnormalities when the face is in the upside down orientation, but can immediately spot the changes when the face is right side up

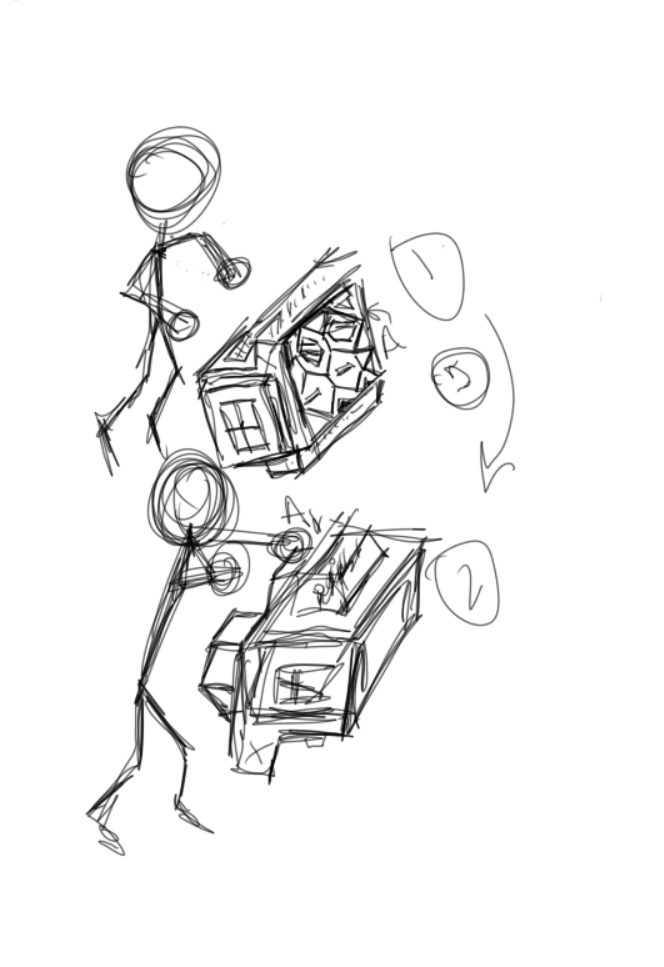

Application: Prototyping a Directionless Object

For my final project, I will develop a prototype demonstrating directionless design principles. This prototype will either take the form of a multifunctional workstation or an object that appears visually upright from multiple orientations. Key design considerations include:

- Symmetry and Geometric Adaptability: While symmetry enhances bidirectional readability, it is not a necessary condition. Instead, intersecting solids and constructive geometries—where forms are derived from boolean intersections—will be explored.

- Visual Perception and Orientation Cues: By integrating neuroaesthetic insights, the design will incorporate patterns and color schemes that facilitate perceptual adaptability in different orientations.

- Functional Ergonomics in Microgravity: The object will be designed to maintain usability regardless of the user’s positioning, ensuring that no single orientation is privileged.

References

Magsamen, S., & Ross, S. (2023). Your Brain on Art: How the Arts Transform Us. Random House.

Thompson, P. (1980).

Margaret Thatcher: A new illusion. Perception, 9(4), 483-484. https://doi.org/10.1068/p090483

2 Comments. Leave new

Your concept of “directionless design” is fascinating, especially how you connect microgravity challenges to neuroaesthetics and visual perception. The ambigram analogy and Thatcher effect add great depth to your argument. For your prototype, how will you test its effectiveness in a gravity-bound environment? Looking forward to seeing it take shape!

Andrea,

This is a really cool concept that I had no idea about. Thanks for sharing this information, I found it to be really insightful! I never knew this about the human brain and really love the concept to make something visually pleasing no matter the orientation. Do you plan to create your final artifact for a microgravity environment?