Brutalism was a modernist movement that focused on bringing in a new era of architectural design, leaving the war-torn 1940s in the past. It is most commonly found in architecture but can also be seen in fashion, art, and other forms of expression. This design style began in England in the 1950s, as they were rebuilding after World War II.

Brutalism focuses on showcasing building materials and structural elements, without adding additional decorative features. Notable characteristics include large amounts of concrete, steel beams, glass, and exposed brick, all arranged in very dramatic and angular designs. It is a stripped-down version of a building with an intentional lack of color; this allows the natural materials to show through in the design. Brutalism lost some popularity around the 1970s when brutalist buildings were seen as cold and overpowering.**

Figure 1: The Economist Building (London, England)

Leading figures in the brutalism movement include Alison & Peter Smithson. Above is an example of one of their designs, The Economist Building in London. The building was designed with rough concrete and glass to make up much of the exterior. The Smithson’s also were the designers who created the theory “Streets in the Sky”, the concept that buildings would have pedestrian areas raised above the roads designed for cars. This was seen in The Economist Building, where they incorporated a plaza between two buildings, allowing users to be outside and above street-level.

Figure 2: Royal National Theater (London, England)

Above is the Royal National Theater in London. The exposed concrete, bold towers, and angular design are very typical elements of Brutalism. This design is functional and “no-frills” but still stands out in a unique way.

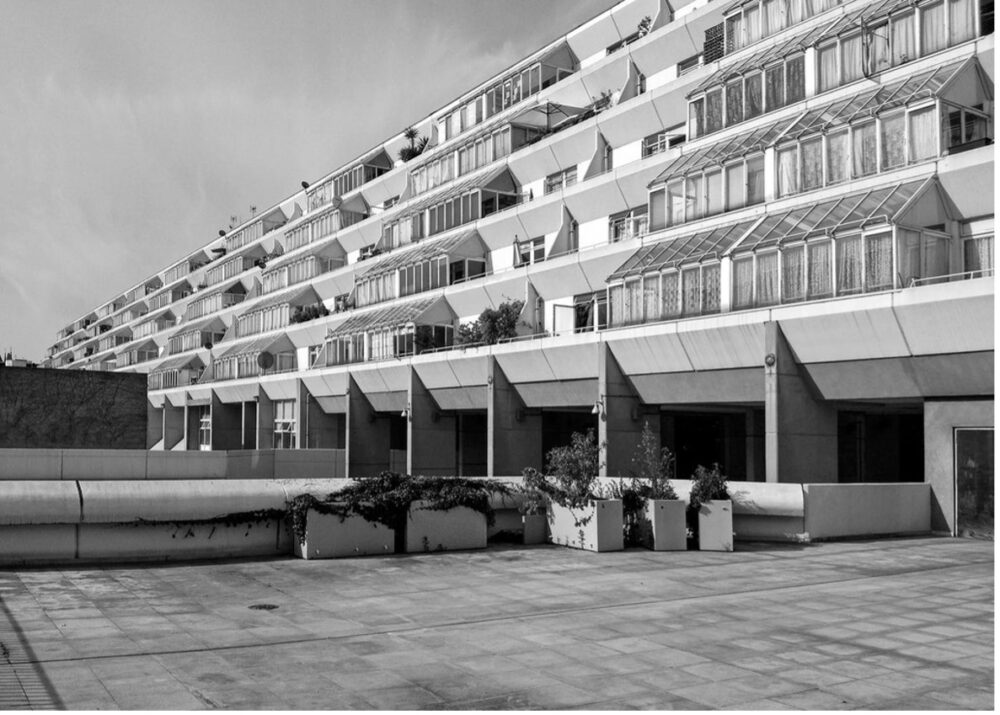

Figures 3 & 4: Brunswick Centre (London, England)

Another example of brutalism is the Brunswick Centre (above), designed by Patrick Hodgkinson. It has a terrace-like structure made mostly of concrete. Concrete was a very realistic building material for England post-war, as it was affordable and ideal for a recovering economy. The Brunswick Centre makes a strong architectural statement and is an infamous building in London.

Some local examples of brutalist architecture include the NCAR Mesa Laboratory Building and our very own CU Engineering Center.

Figure 5: NCAR Mesa Laboratory (Boulder, CO)

The NCAR building features sharp, concrete shapes and extreme cutouts that are typical of brutalism. The building is slightly different as it uses a red-tinted concrete versus the typical gray-toned. This helps the building blend with its surroundings, which is a benefit given its highly visible location on the otherwise untouched Boulder skyline.

Figure 6: CU Boulder Engineering Center (Boulder, CO)

The CU Engineering Center was finished in 1966, during the peak of brutalism. The Engineering Center incorporates many brutalist design aspects with the concrete construction, unusual angular design, and minimalist incorporation of windows. There are also areas with rough and unfinished stonework, fully embodying the aesthetic. The only part that does not fully fit is the terracotta roofing, which is a design that is found throughout almost all buildings around campus. This was kept standard even in the Engineering Center, helping the design blend in with the campus even though it stands out in other ways.

**Edit (1/28/2025): More Information on the Decline of Brutalism (below)

The popularity of brutalism saw a steady decrease in the 1970s and 1980s due to a combination of factors. One major cause was the shift in architectural trends. The public wanted to see more visually inviting buildings versus the cold exterior common with brutalism. The public perception of brutalist buildings also caused them to be associated with social issues of the time like crime, vandalism, and decay. Additionally, the upkeep of the buildings was costly due to aging and signs of wear & tear on the porous, exposed concrete.

Sources

Information

https://www.archdaily.com/645128/spotlight-alison-and-peter-smithson

https://gd2tech2014.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/bernardy_hway_palzer.pdf

Images

[1] https://www.archdaily.com/645128/spotlight-alison-and-peter-smithson

[2] https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/london-brutalist-architecture

[3] https://bluecrowmedia.com/blogs/news/brutalist-architecture-in-london-today

[4] https://bluecrowmedia.com/blogs/news/brutalist-architecture-in-london-today

[5] https://mgerwingarch.com/m-gerwing/2010/06/03/i-m-peis-ncar-building-boulder-colorado-part-2-ta6z5

[6] https://www.geco.com/Projects/Project-Details/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/985

5 Comments. Leave new

Hello Cecilia, I really enjoyed this blog post! It in many ways mirrors the interest that brought me to my own post about the utilitarian “aesthetic.”

I appreciate your delivery of the scope of this modernist movement, from history and architecture through fashion, art, and expression.

Do you enjoy the non-decorative and dramatic angular designs of this aesthetic? Do you have a favorite among your featured examples?

I appreciate you bringing examples close to home (literally) with the NCAR building. Do you feel as though this design aesthetic was chosen or emphasized deliberately? And perhaps the same with the engineering center on campus?

I found the post to be very well organized and fluid with different subjects and each getting a great explanation and I love the local examples as well. It is a very unique aesthetic and in terms of architecture, the buildings sure catch one’s attention.

Thank you for the feedback!

Cecelia, I appreciate the local connection to NCAR and the CU Engineering center as it helps me to internalize and appreciate the brutalist architecture points that you touched on. One suggestion is you can consider going into greater detail on the factors that contributed to the decline of this aesthetic. Overall, I enjoyed reading about what you found and thank you for sharing!

Thank you for the constructive feedback! I will definitely add more information on the decline of brutalism.