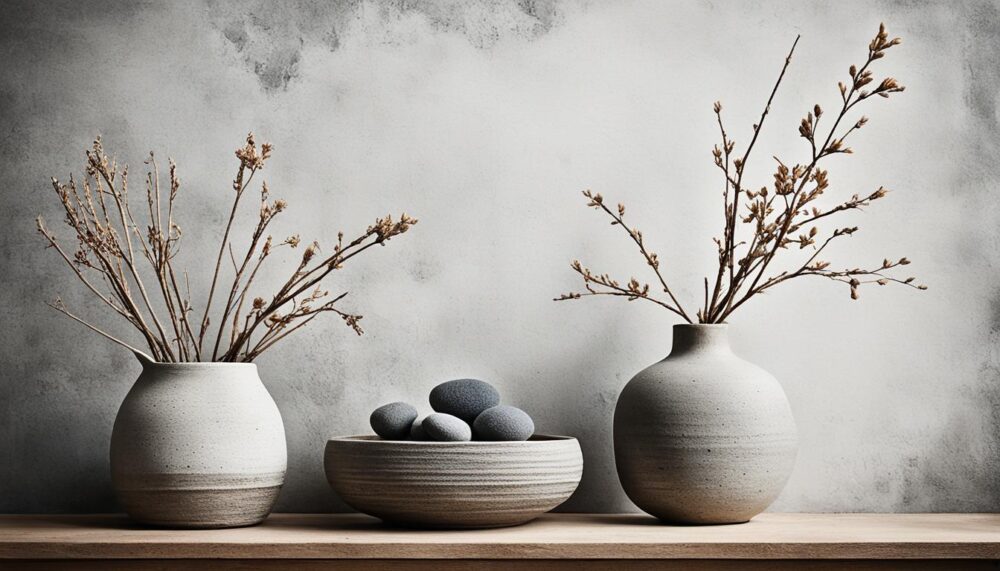

The Wabi Sabi aesthetic is a traditional Japanese aesthetic that is centered around imperfections, modesty, austerity, minimalism, and the integration of nature. The term itself combines “wabi,” which initially described the loneliness of living in nature, with “sabi,” referring to the beauty of aging. The Wabi Sabi aesthetic has been said to represent ancient Japanese values and culture, and its influence can be seen throughout Japan’s history in its architecture, art, engineering, gardens, clothing, and even food. Rooted in Japan’s Muromachi period (1336–1573), it was deeply influenced by Zen Buddhist principles. Figures like Sen no Rikyū (1522–1591), a pivotal tea master, were instrumental in embedding Wabi Sabi into Japanese culture. Through the tea ceremony, he introduced rustic, handmade pottery and neutral tones, emphasizing simplicity, authenticity, and a profound connection to nature. This nature-inspired aesthetic has carried a profound influence on the West, particularly in architecture, art, and philosophy.

Wabi Sabi in Architecture

Wabi Sabi architecture emphasizes harmony with nature, showcasing imperfections and the inherent beauty of natural materials. This approach can be seen in traditional Japanese homes, where unrefined wood, clay walls, and thatched roofs blend seamlessly into their surroundings. Rather than imposing on the environment, Wabi Sabi architecture seeks to coexist with it, often incorporating elements like rocks, plants, and water features to create a sense of fluidity between the indoors and outdoors. Modern interpretations of this aesthetic have influenced architects worldwide, promoting the use of organic materials and designs that foster tranquility and mindfulness. By embracing imperfection and simplicity, Wabi Sabi architecture offers a counterpoint to the sleek, high-tech designs of contemporary urban spaces, creating homes that feel timeless and deeply connected to the earth.

Wabi Sabi in Art

In art, Wabi Sabi celebrates the beauty of imperfection, transience, and incompleteness. Traditional Japanese pottery, such as raku ware, exemplifies this aesthetic with its irregular shapes, natural glazes, and asymmetrical forms. These qualities are not seen as flaws but as reflections of authenticity and individuality. Calligraphy and ink painting also embody Wabi Sabi principles, using spontaneous, unpolished brushstrokes to convey emotion and the impermanence of life. The aesthetic’s influence extends to contemporary art, where it inspires creators to explore themes of decay, impermanence, and the passage of time. By embracing flaws and imperfections, Wabi Sabi art encourages a deeper appreciation for the ephemeral nature of existence.

Wabi Sabi Philosophy

At its core, Wabi Sabi is a philosophy that challenges the modern obsession with perfection, permanence, and materialism. It encourages mindfulness, gratitude, and acceptance of life’s imperfections. Rooted in Zen Buddhist teachings, it invites individuals to find beauty in simplicity, to value the natural cycle of growth and decay, and to embrace the ephemeral nature of all things. Wabi Sabi philosophy resonates deeply in a world increasingly dominated by fast-paced consumerism, offering a reminder to slow down, appreciate the present moment, and seek fulfillment in the modest and the unadorned. Its principles have influenced Western minimalism and sustainable living practices, promoting a lifestyle that values quality over quantity and depth over superficiality.

Conclusion

The Wabi Sabi aesthetic is more than a style; it is a way of seeing the world that values authenticity, impermanence, and the quiet beauty of the imperfect. From architecture to art to philosophy, it offers timeless lessons on finding harmony within ourselves and our surroundings. As its influence continues to grow globally, Wabi Sabi serves as a gentle reminder to cherish simplicity, embrace imperfection, and connect deeply with the natural world. In a fast-moving, perfection-driven society, the wisdom of Wabi Sabi provides a path to balance, mindfulness, and a more meaningful way of living.

Bibliography

- Juniper, Andrew. Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence. Tuttle Publishing, 2003.

- Koren, Leonard. Wabi-Sabi for Artists, Designers, Poets & Philosophers. Imperfect Publishing, 2008.

- Richie, Donald. A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics. Stone Bridge Press, 2007.

- Suzuki, D.T. Zen and Japanese Culture. Princeton University Press, 1970.

- Takeda, Kiyoshi, and Charles Shiro Inouye. Wabi Sabi: The Art of Everyday Life. Periplus Editions, 2014.

- Tanizaki, Jun’ichirō. In Praise of Shadows. Vintage, 2001.

2 Comments. Leave new

I really enjoyed reading about this aesthetic. Your writing was clear, concise, and packed with interesting facts. Additionally, the images you chose are visually stunning and work well together. By the end of your post, I felt I had an excellent, base-level understanding of the aesthetic. Your post was so thorough and well-written that I’m not sure I have any critiques. Well done!

This is a very interesting aesthetic! I love the combination of nature and the appreciation of imperfection and simplicity. I also liked your explanation for how Wabi Sabi was created. It’s clear that some of those initial Zen Buddhist ideals are still a prominent part of the aesthetic. I’m curious about some of the intricacies of the Wabi Sabi. You mentioned that it influenced some of the fashion and food throughout Japan’s history. Do you have an example of what this looks like? I also noticed that your third to last image includes a vibrant purple, but it seems as though this aesthetic highlights more muted, natural tones as shown in your other photos. What colors are commonly used with this aesthetic? Are brighter colors often incorporated as well?