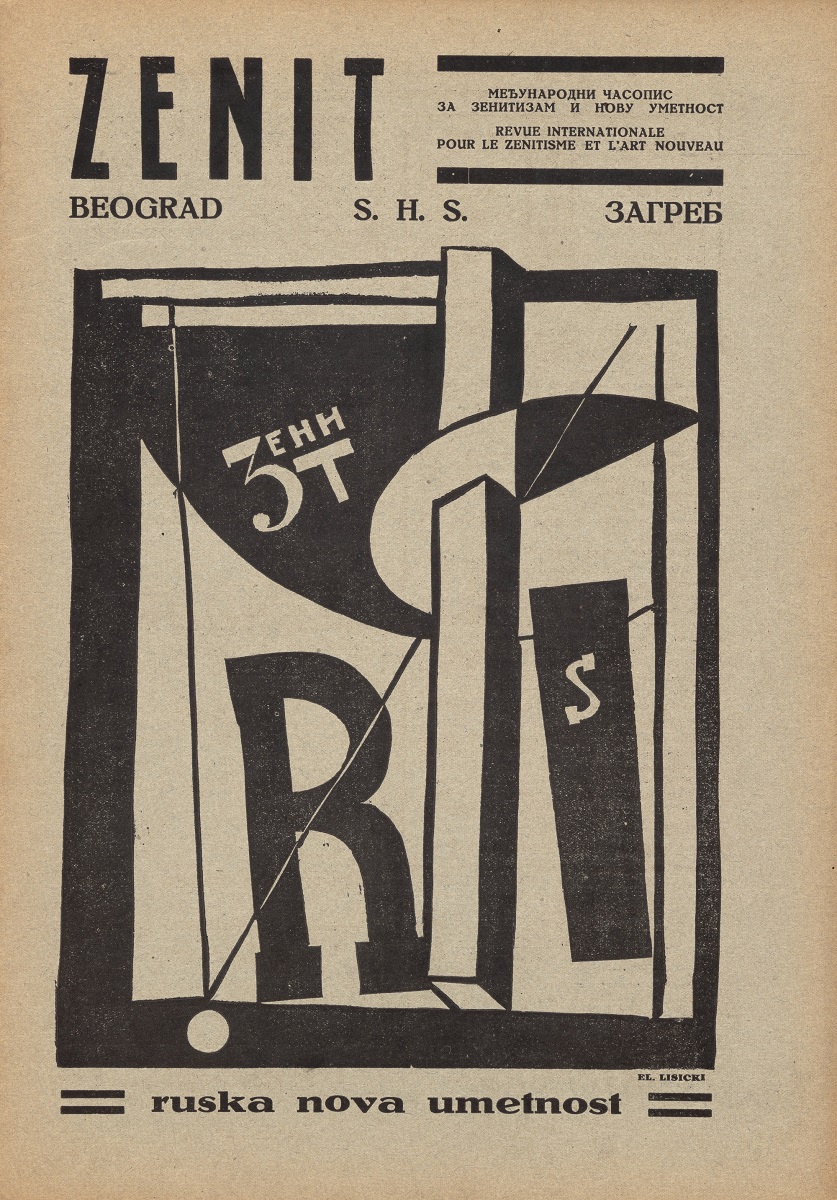

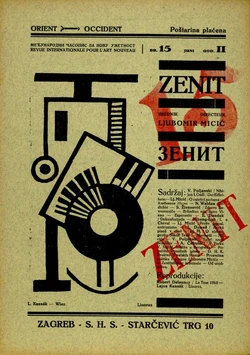

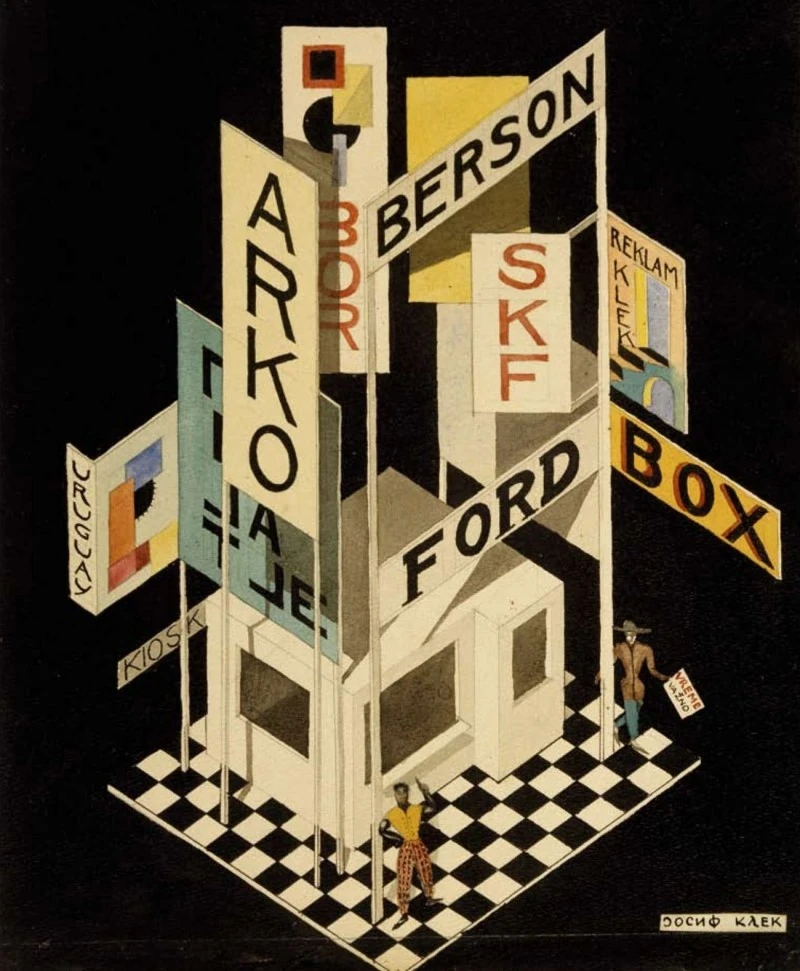

Following the end of World War I, the former country of Yugoslavia was founded by the joining of the Kingdom of Serbia and the State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs. During the war, these former states saw devastation and the losses of millions. Seeing first hand the desolation of Europe, Ljubormir Micić sought to unite all of Europe, rather than continue the Eastern versus Western European which pervaded most all of Europe. In 1921, a magazine under the name of Zenit was published by Micić. This magazine held anti-war and pro-humanitarian views, rejecting the traditionalist views of European culture by incorporating aspects of both western and eastern European art movements, such as Cubism and Dadaism. From this magazine came the aesthetic of Zenitism, an avant-garde movement characterized by abstract use of shapes and checkered patterns often to depict urban settings and their inhabitants. The journal Zenit sought to be both the first Balkan magazine in the west, as well as the first western magazine in the Balkans.

Philosophy

At the core of Zenitism lies the rejection of a politically unaligned Europe and the valuing of human life. Zenitists believed that the now war torn Europe could be overpowered by what they referred to as the Barbarogenius, a modern primitive similar to the stereotypes held by the west of the Balkans. A view born to increase nationalism within the newly formed Yugoslavia and prevent further spreading of negative stereotypes within Yugoslavia and Europe as a whole. While this philosophy is not readily apparent at first sight, the combination of multiple European art movements and the philosophy of the magazine itself help to relay the idea of unification between cultures.

Influence

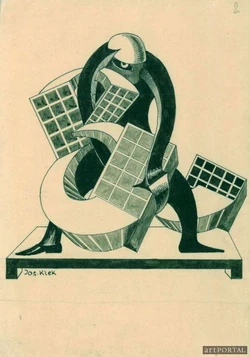

Ultimately, the Zenit magazine was halted after 44 published issues in 1926 due to censorship from the Yugoslavian government. While this movement was short lived, Zenitism is still considered the most relevant art movement from the Balkans. The magazine gained international recognition, influencing the rise of the avant-garde movement in Europe. The Zenit magazine covered everything from poetry and music to architecture and politics. Platforming artists and writers from all across Yugoslavia, as well as others across western Europe and Russia, often printing these passages untranslated. These journals were accompanied by the illustrations of Jo Klek and Mihailo Petrov with special covers done by young Czech and Russian artists. The Zenit was a gathering place for all to share their own perspectives of the world, uniting readers through their shared love of literature and the fine arts, regardless of their nationality.

References

Glišić, Iva, and Tijana Vujošević. “(PDF) Zenitism and Orientalism.” ResearchGate, Jan. 2021, www.researchgate.net/publication/355315705_Zenitism_and_orientalism.

Heller, Steven. “Zenit.” PRINT Magazine, 23 Oct. 2023, www.printmag.com/daily-heller/zen-zenit-zenitism/.

“Zenit.” Monoskop, monoskop.org/Zenit. Accessed 22 Jan. 2025.

Images Derived From

[1] Wiki, Contributors to Aesthetics. “Zenitism.” Aesthetics Wiki, Fandom, Inc., aesthetics.fandom.com/wiki/Zenitism. Accessed 22 Jan. 2025.

[2] Heller, Steven. “Zenit.” PRINT Magazine, 23 Oct. 2023, www.printmag.com/daily-heller/zen-zenit-zenitism/.

[3] Heller, Steven. “Zenit.” PRINT Magazine, 23 Oct. 2023, www.printmag.com/daily-heller/zen-zenit-zenitism/.

[4] “Centenial of Zenit Magazine.” Galerija Rima, galerijarima.com/en/article/exhibition/past-belgrade/centennial-of-zenit-magazine-19211926.html. Accessed 22 Jan. 2025.

4 Comments. Leave new

I like that you selected a pretty niche topic because I really enjoyed learning about this aesthetic and I had never heard of it before. Movements like cubism and Dadaism received a lot of attention but its really interesting to look into more unique movements like this one that may have been influenced by bigger aesthetics. I really like how cohesive all the magazine covers are even though the designs vary quite a lot. One thing I’m wondering is what kind of publications did they have in the magazines and did it help unite eastern and western Europe?

Thanks Ellyse, the magazines themselves were kind of a journal, where people would submit poetry or short passages about anything from politics to a play that was popular at the time. While I don’t believe that this movement had a direct impact on the unification of the east and west, it has been attributed as one of the movements that brought the avant-garde movement to east Europe, which was tied with anti-war sentiments.

The topic you selected is very interesting. I would have never known Yugoslavia was founded until now. It is also interesting to see how such a devastating event can cause a whole new form of art. Also, the images you chose from the Zenit Magazine portray the aesthetic well. I know Zenitists started this form of art, but it would be nice to know the names of some more artists that influenced this aesthetic. Who was the first person to create this sort of art?

Hi Kalin, thank you for your comment. As I was exploring this topic I really only found two artists who were well known for their Zenitism style of art, Jo Klek and Mihailo Petrov. While the origin of this aesthetic can most aptly be attributed to Ljubormir Micić, as he started the Zenit, it was the works of Klek and Petrov that inspired other artists of the time, such as those attributed to the magazine covers above. However, due to the censorship of the Yugoslavian government the Zenit style seemingly died out fairly quickly, however from what I read it led to the popularization of more experimental art forms with humanitarian messages in eastern Europe.