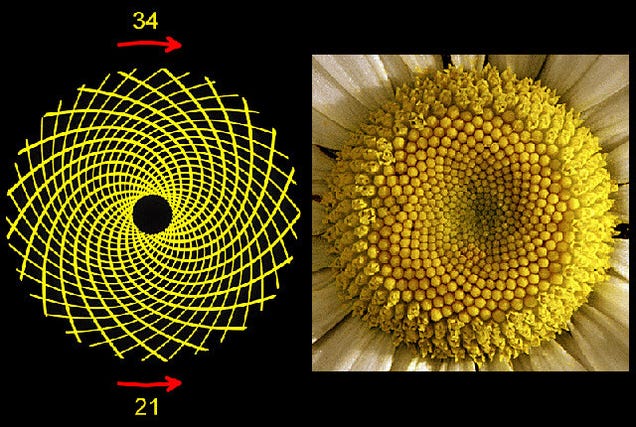

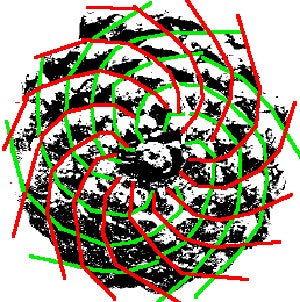

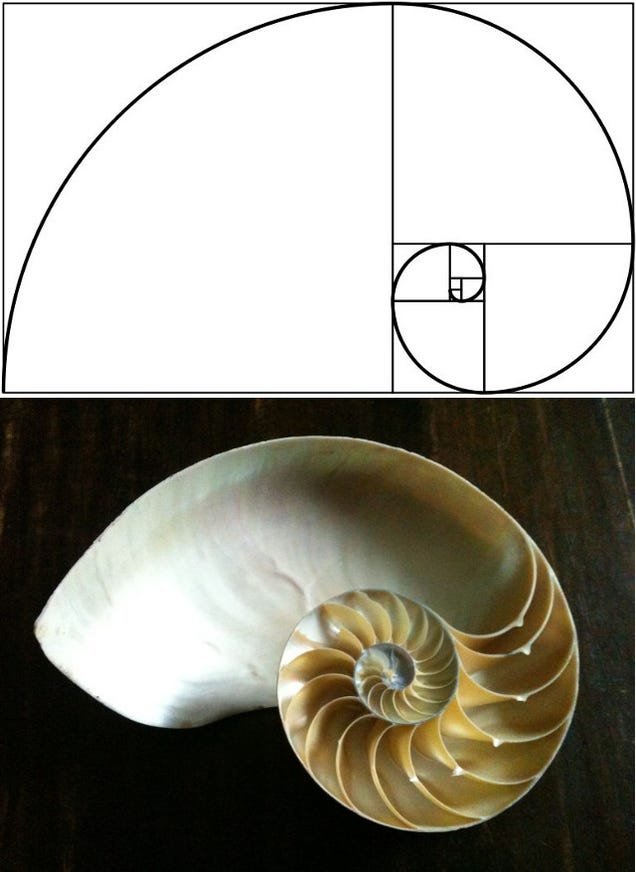

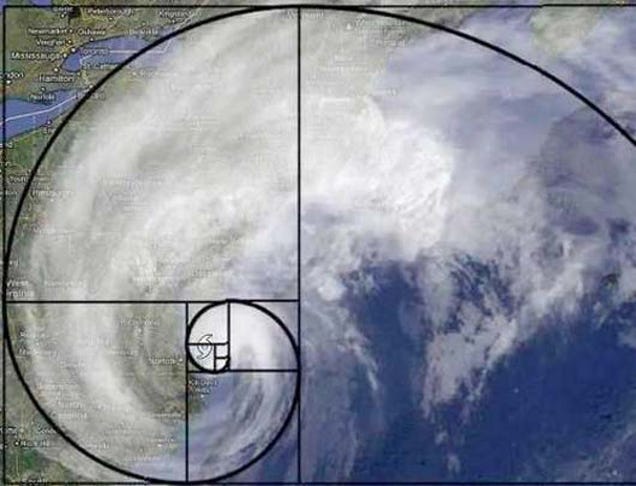

The golden ratio is a ratio of 1 to 1.618 that seems to be abundantly demonstrated in nature. This is mathematically represented by the Fibonacci series, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 – each number being the sum of the two previous numbers. The ratio of one number to the next number approaches the golden ratio. The following is a list of examples of the golden ratio as seen in nature:

Flower Pedals

Seed heads

Pinecones

Fruits and Vegetables

Tree branches

Shells

Spiral Galaxies

Hurricanes

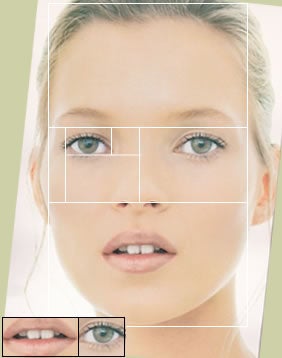

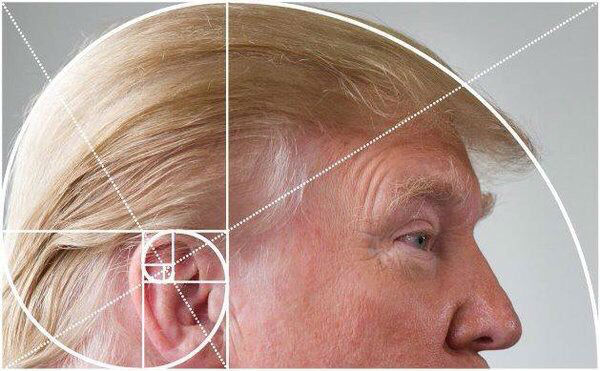

Faces

Fingers

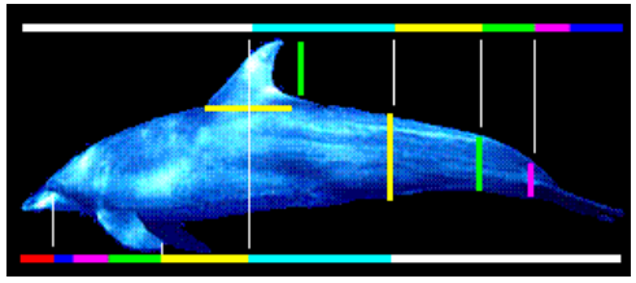

Animal Bodies

Reproductive dynamics

Animal fight patterns

Uterus

DNA Molecules

This ratio has also been called the divine proportion, being used as evidence that the universe is designed by an intelligent being with this ratio as a blueprint.

This ratio has also been used in many works of art. Some of the most famous examples include the Acropolis of Athens, the Parthenon, Vitruvian Man, Mona Lisa, and even musically in Claude Debussy’s Image: Reflections in the Water.

It seems that this ratio pleases the human eye, but the reason remains a mystery. One theory, according to Adrian Bejan, a professor of mechanical engineering at Duke University, is that the human eye has developed to interpret images featuring the golden ratio faster than any other. Bejan makes the comparison to the animal world, where their eyes have developed according to their habitat. An antelope has horizontally oriented eyes that can scan the horizon quickly, being able to identify land predators (but not air or underground predators). Similarly, humans have developed to efficiently take in information when they resemble the golden ratio, pleasing our brain and being interpreted as “beauty.” Because vision and cognition co-evolved, visual efficiency has been a key factor in the development of the brain’s architecture.

To add to Bejan’s theory, I believe that the golden ratio is pleasing to humans because it represents the ultimate familiarity with the world they evolved in. In the article “The Four-Letter Code to Selling Just About Anything” by Derek Thompson, it is claimed that people want things that are familiar, yet novel. The familiarity is comforting because it represents elements that haven’t (obviously) killed us yet. Novelty is desired because it keeps us intrigued, leading us to new experiences, perspectives, and creativity, which fuels advancement of humankind.

As mentioned above, the golden ratio is abundantly present in our universe. To represent that ratio in artwork is to touch the human psyche that has developed over thousands of years in a way that defies logic. It’s comforting to the limbic brain because it lets us know that the artwork (with the golden ratio) we’re looking at is from the world that we evolved in, one that has kept our species going.

References:

http://io9.gizmodo.com/5985588/15-uncanny-examples-of-the-golden-ratio-in-nature

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_works_designed_with_the_golden_ratio

http://monalisa.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/02-ml-ps-emlgoldenspiral-03-940×1234-228×300.jpg

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/dec/28/golden-ratio-us-academic

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/01/what-makes-things-cool/508772/

3 Comments. Leave new

[…] Aesthetics of Design (Aesthetic Exploration: The Golden Ratio – Aesthetics of Design (aesdes.org)) […]

[…] https://www.aesdes.org/2017/01/24/aesthetic-exploration-the-golden-ratio/ […]

Loved the post. I’ve heard of this before but I have never looked into it myself. For the golden ratio in art, particularly the Mona Lisa, do you think that the golden ratio was used intentionally or simply coincidence that it worked out?